Case Study

35mm v Digital

Introduction to Digital Cinema: 35mm v Digital

In this blog, we explore technology that makes digital cinema possible, the processes that get films from studio to screen, and match all that theory with some practical operational tips.

The beginnings of moving pictures.

From the beginnings of moving pictures in the early 1900s through to the early 2000s, the basic principles behind projecting an image onto a screen changed very little. Reels of film were laced into a projector, which passed the film in front of a lamp and through a lens that blew the image up onto the screen.

Distributors would send reels of 35mm film to exhibitors, each of which could hold about 20 minutes. This meant that for any given feature, a distributor would have to send between four and ten of these heavy reels to every cinema to show a feature. Producing copies and shipping them was quite expensive, which sometimes limited the number of prints available and consequently meant that prints were often cleaned and re-used at other cinemas in other territories.

Platters and rollers.

Over time, the methods of projecting evolved. From multiple projectors per screen and reel to reel performances, to the adoption of platter systems that made the multiples a workable reality.

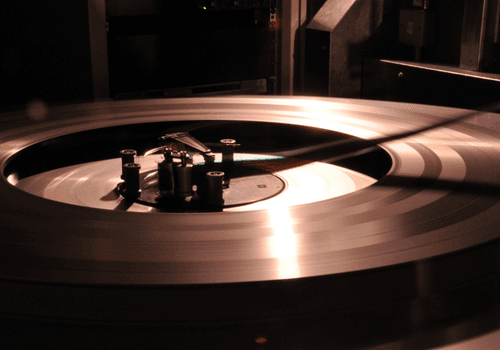

Once the print arrived, the projectionist spliced all the reels together, added any trailers/ads so that it could be shown uninterrupted, and transferred the resulting thousands of feet of film onto what was called a platter. Platters were large flat disks that allowed the film to be played out without needing a projectionist there to manually switch between reels.

Platter example. Credit: Alexa Raisbeck

The projectionist would then lace the film into the projector through a system of rollers that might span a few metres, and sometimes passing it through a static cleaner that would help remove dust before it entered the projector, careful not to scratch it at any stage.

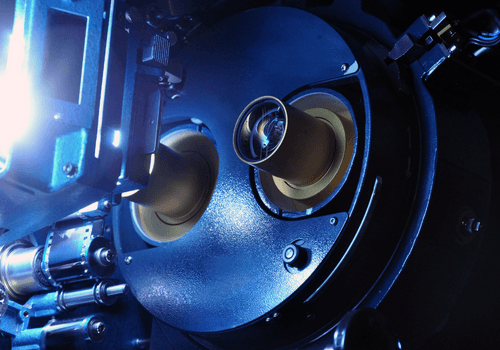

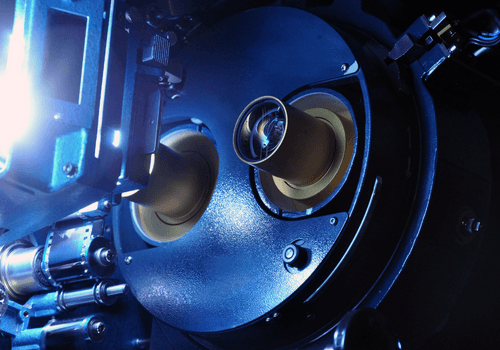

Passing through the projector.

The film would then be passed through the projector head in front of a Xenon arc lamp (still commonly in use today) and synchronised with a shutter that would obscure the light from the lamp between frames of film for the transition. This flicker between a dark screen and the image at the industry standard rate of 24 frames-per-second (FPS) tricks the brain into thinking it is seeing a moving image, instead of individual frames. After the film passed through the projector it would be spooled directly onto another platter, ready to be shown again.

Each print would typically only be run in one auditorium at once. However, a practice called interlocking was also common and involved feeding the film from the platter into a projector, which would then feed directly into another projector. This allowed a single print to be shown in multiple auditoriums simultaneously but presented a higher risk of damaging the print.

The sound was encoded right onto the film strip along the edges near the perforations and would have been read by a digital soundhead, usually mounted above or below the projector head.

Projector turret. Credit: Alexa Raisbeck

Converting to digital.

The 35mm set-up was complex, expensive, and required a lot of attention from experienced projectionists. It afforded cinemas little operational flexibility, incurred distributors significant expenses, and wasn't very adaptable to new technologies.

Digital presented clear monetary advantages to distributors as producing and transporting a hard drive with a feature was significantly cheaper than the equivalent reels of film. Customers would experience a more consistent image and sound quality, as well as better premium options like 3D.

Unlike projecting a physical film print, where even when the highest levels of care and attention are taken, a digital print will never degrade or exhibit signs of wear. A performance of a digital film means that the presentation quality is the same weeks after a release as it is on the opening night.

The advantages digital would present over exhibitors' day-to-day operations were also considerable, however, spending a large amount of money to replace 35mm projectors that still worked was unappealing to cinemas as they doubted they could earn the return on investment.